Jackets and pants

Most riders wear a motorcycle jacket (97%) but fewer wear motorcycle pants (45%). This is despite the fact there is actually far more risk of injury to the legs than to the upper body or arms. Four out of five motorcycle casualties (81%) have injured their legs and a third have broken bones (32%). Arm injuries are less common (56%) and less likely to involve fractures (17%).

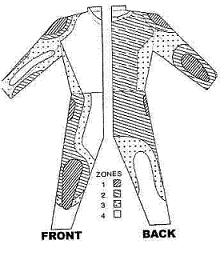

You need different levels of protection for different parts of your body according to the level of risk. Injury risk zones have been identified through the analysis of crash damaged riding gear (Woods, 1996).

These zones form the basis of the European Standard and are useful for identifying where you would benefit from high levels of protection, and where you can afford to have more breathable and flexible fabric. The first step is to use the injury risk zone diagram to check the design and construction of the jacket or pants.

See What parts of your body should you protect? for the injury risk zone diagram.

Is the material used appropriate for each zone?

Zone 1 is the area of the most frequent impacts. Are there impact protectors in each Zone 1 area– that is at the knees, hips, elbows and shoulders?

Are all Zone 1 and Zone 2 areas well protected with high abrasion resistant materials? The minimum requirement under the EU standard is for 4 seconds abrasion resistance. Multiple layers may be more effective than a single layer of extra thick leather.

Zone 3 is a moderate risk area and should have abrasion resistant material. The EU standard requires a minimum of 1.8 seconds abrasion resistance.

- Zone 4 is a relatively low risk area. The material here can provide ventilation and elasticity, however it should still have some abrasion resistance qualities. The EU standard requires a minimum of 1 second abrasion resistance, where as ordinary denim jeans only provide 0.6 seconds.

Choosing the right suit

It is not as simple as trusting the experience and reputation of the manufacturers.

Recent independent tests by Motorcycle News (MCN, 2003), in the UK found only 4 out of 18 leather suits from the major European manufacturers, passed all the tests against the European Standard. Twelve of these suits failed the burst test due to either thread and/or leather failure and impact protectors failed in eight suits.

Price is no indicator of protection. The leather suits in the MCN tests ranged from AU$600 to AU$3,000. Some expensive made-to-measure suits failed, while other suits that cost a quarter of the price, passed. (MCN, May 2003).

A similar review of textile jackets by Ride magazine in the UK also showed that price and protection are not linked. They tested 51 jackets costing between AU$160 to AU$1,050. The results found 46 of the 51 jackets above average for impact resistance, while only 36 scored above average for abrasion resistance. As with the leather suits, the worst result was for burst resistance, with just 10 of the 51 suits judged to have adequate seam strength, including the most expensive suit in the test group. (Ride, January 2003).

However, looking back over similar independent test results for the past 10 years, it is apparent that manufacturers have responded to calls for better protection. Continuing research, new materials, and improved processes, will see superior equipment become available, but only if the pressure of demand is maintained.

Most manufacturers are finally including impact protectors in all the right places. The abrasion resistance scores for textile jackets have also improved significantly. However it is pointless to have high abrasion resistant materials (leather or textile), if the stitching fails and the suit bursts apart when you hit the road. Quality of construction is critical.

back to top of page

What should riders look for?

In Europe, if a jacket or pants is labelled CE EN 13595, then you know it has been tested and complies with the EU Standard for abrasion, impact, cut and burst resistance which are the key measures of injury protection.

If a garment has not been tested, you cannot tell its protective value by just looking at it. However, there are some design and construction features that may help you recognise suits that are more likely to do the job.

Many riders wear less protection in hot weather. See the section on what to wear for protection in the heat, cold and rain. Protection from the weather and Protection from SMIDSY (Sorry Mate I Didn't See You).

The first decision is whether to buy leather or textile.

Leather has been the traditional choice for motorcyclists because of its high abrasion resistance, however, all leathers are not equal. As the MCN tests illustrate, just because it is leather does not guarantee your protection. It depends on the type and grade of leather and how it has been treated. In abrasion tests conducted on 29 different types and grades of motorcycle leather, only 17 passed for use in Zones 1 and 2. (SARTRA, 2002).

There are now many textiles that are promoted as abrasion resistant, plus having the added benefits of being lightweight and flexible and providing better ventilation and waterproofing.

How good are the non-leather textile alternatives?

It's hard to say. We have found only 5 textile garments that have actually passed independent tests against the EU Standard. This doesn't mean the other products don't or wouldn't pass the Standards, but we have yet to see the evidence.

Note: Jackets with impact protectors will often have CE labels (EN 1621-1 or EN 1621-2). These labels only refer to the impact protectors, they do not include the jacket, which must be labelled EN 13595 if it complies.

It is worth noting that none of those that have passed the tests rely on a single layer of material to achieve the result, they all employ a number of layers, each with a different job.

Under the EU Standards, material used in motorcycle protective clothing must have abrasion resistance of between 4 and 7 seconds for use over the high impact areas of the body (Zone 1 and 2). Just to put this in context, a single layer of 1.4 mm cow hide will last 5.8 seconds, while 200 gsm denim (or your standard jeans), will last just over half (0.6) of a second (SATRA, 2002).

Tests conducted at the British test laboratory SATRA (SATRA, 2002 and at the Melbourne Institute of Textiles (Standards Australia, 2000), found many of the modern textile alternatives fail to meet the standards when tested as a single layer.

This does not mean that such fabrics are necessarily unsuitable, because it depends on how they are used. Fabric weight, coatings or finish can make a significant difference to test results. The design and construction of the garment is also crucial in determining its protective value.

The only way to determine whether a particular fabric is suitable for motorcycle protective clothing is to test samples of the completed garment. That is why the European Standard labelling system is so useful to motorcycle consumers. However given that many of the products available in Australia, are not subjected to the EU testing system, here are some design features that will help to guide you in your selection.

Fit

It may seem unnecessary to have to say this, but clothing should fit comfortably when you are in riding position and still be reasonably comfortable for moving around when not on your motorcycle.

If it is tight, it may become distractingly uncomfortable and fatiguing or even restrict blood flow.

- If it is too loose it can billow and flap which is also distracting and fatiguing. See Protection from the weather.

The smoother the exterior shell of your garment, the fewer tear and snag points. Avoid straps or external pockets that may catch on your bike, the other vehicle or objects on the road. You don't want to be dragged down the road or snagged by something.

Large panels of fabric mean fewer joins and seams, which can burst open as you hit or slide along the road. So the fewer openings and joins in the garment the better.

Decorations such as metal buckles and other hard or sharp objects not only scratch your paintwork in normal use, but can twist around and end up penetrating you. They should not be used in impact zones, nor anywhere they might cause injury. Think about what you keep in your pockets for the same reason (pens, keys and phones).

Impact protectors only work if they remain in place in a crash. Check to see if you can push them around when your jacket/ suit is fully fastened. If you can move them, then there is a good chance they will not be where you need them if you crash.

- Lining in Zones 1, 2 and 3 should be slippery material to allow your body to slide against the external shell, this reduces the risk of your skin being penetrated by sharp objects.

- Lining should have a high melting point, to ensure it does not melt into your skin under friction from road surfing. Check the label.

Zips should not be used in Zones 1 or 2. Check the Zones in Protection from injury.

All zips should be covered to prevent contact with the road and have an internal flap of the same material to prevent the zip from injuring the rider in an impact.

- Sleeves and trousers must have some sort of strap, zip or other means of locking them on to your wrist and ankles to prevent them from riding up in a crash. Fastenings should be on the inside of the wrist or ankle.

Will the seams burst when you hit the ground? Seam failure is the most common failing in motorcycle clothing. The seams in these leathers were glued and then stitched with only a single row of stitching. The seams bust on impact when the rider hit the ground. (Photo courtesy of Two Wheels.)

Testing is the only way to be sure that seams are strong enought to hold, but you can check for the following:

Seams in Zones 1, 2 and 3 should have at least one row of concealed or protected stitching, to hold the seam together after the visible stitching has been worn away against the road surface.

Check the stitching. It should be regular with no dropped stitches, which indicate a potentially weakened seam.

Leather should have 11-14 stitches per 5 cm, fabric should have 13-16 stitches per 5 cm (Standards Australia, 2000, p 22). Too few stitches, means the seam will be too weak, but too many stitches will actually weaken the fabric.

Additional layers should be double stitched.

- Additional layers MUST be stitched on top of the main protective layer - see diagram A, rather than a separate double section that is inserted into the garment (see B). Check inside the garment to ensure there is no gap in the main protective layer. You may need to feel through the lining.

right

Back to - Which parts of your body should you protect?.